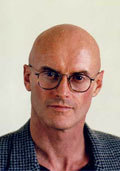

Ken Wilber

Ken Wilber |

This article comprises an adapted and amplified version of chapter 1.9 in my Minds and Sociocultures Vol. One: Zoroastrianism and the Indian Religions (1995), pp. 101-127. That book attempted a detailed and historical coverage of religious traditions, as distinct from the treatments found in popular "new age" and "transpersonal" literature. The section on Ken Wilber, part of the introduction to that work, is considered the first detailed critique of early Wilber books.

CONTENTS KEY

1. Perennial Philosophy: Wilber Replaces Huxley

3. No Boundary

5. Up from Eden Versus the Archaeology of Sumer

6. Transpersonal Assumptions and Deceptions

1. Perennial Philosophy: Wilber Replaces Huxley

The American writer Ken Wilber gained popular celebrity as a commentator on the perennial philosophy. Certain of Wilber's emphases distinguished him from the Human Potential Movement; for instance, he repudiated the transpersonal relevance of the Jungian archetypes. Jung asserted that: "Mystical experience is experience of archetypes." (1) Wilber qualified this to mean "lesser mysticism."

Wilber's transpersonalism was nevertheless convergent to a considerable degree with alternative therapy, a commercial vampire persisting today. Moreover, Wilber's version of the romantic "perennial philosophy" can be viewed as incomplete, and also incorrect on numerous points of exegesis. In popularity, the Wilber theory replaced the version of British novelist Aldous Huxley (1894-1963), whose format is very minimal in definition, and ultimately misleading, not least because Huxley became a drug ingester.

The first of Wilber's well known books was The Spectrum of Consciousness (1977). This commenced with a statement of the basic thesis supplied, affirming that the different channels of psychology, psychotherapy, and religion are "not contradictory but complementary." The book thus promoted a synthesis "that values equally the insights of Freud, Jung, Maslow, May, Berne, and other prominent psychologists, as well as the great spiritual sages from Buddha to Krishnamurti." (2) The validity of a subject like Gestalt Therapy is not questioned, and the subject of "great spiritual sages" left unclarified. The complementary nature of these diverse subjects is much in query.

A pronounced relativism is expressed in relation to the ultimate "Level of Mind" envisaged, in which context Wilber states: "Brahman is not a particular experience, level of consciousness, or state of soul - rather it is precisely whatever level you happen to have now." (3) This is a very casual definition of Brahman, far more closely resembling Jung's version of the atman than the purist Advaita concept of moksha. The "now" in Wilber's definition is reminiscent of Krishnamurti's emphasis, proving very assimilable to Gestalt Therapy.

In the Wilberian spectrum model, there is no attempt at history of the "perennial philosophy," but instead a series of phenomenological statements based upon presumed authorities like Krishnamurti and Bubba Da Free John (Adi Da Samraj). Many thousands of people who heard Krishnamurti's public talks, and who read his books, were misled by certain of his key emphases. Krishnamurti denied the relevance of a developmental path, a convenience that became an increasing fashion in the New Age, which he influenced to no small degree. If there is no demanding path to truth, the claiming of truth is far more likely to be a deceit.

Krishnamurti (1895-1986) claimed to experience samadhi, a word variously translated and currently meaningless. By the time he associated with Aldous Huxley in California during the Second World War, Krishnamurti was in the habit of lying to some of his intimates. According to his own admission, this failing arose through fear. (4) His private life was not in accord with his preaching. Yet Huxley's version of the perennial philosophy is strongly associated with a glorification of Krishnamurti, who was much admired by Huxley from 1938, at a time when the English writer settled in California.

In The Spectrum of Consciousness, Ken Wilber extolled Krishnamurti as the incredible man whose discourses had been compared by Aldous Huxley to those of the Buddha. More realistically, Krishnamurti led thousands of people to believe that there was no "path," producing a breed of "eternal now" enthusiast. "The real is near you, you do not have to search for it; and a man who seeks truth will never find it." This well known axiom of Krishnamurti was quoted approvingly by Wilber, who facilitated beliefs creating a disastrously complacent effect.

In his preface to The Spectrum of Consciousness, Ken Wilber described that book in terms of a "synthesis of psychotherapies East and West." It is not therefore a discussion of the fabled and elusive perennial. Psychotherapy is not typically striving for truth, instead so frequently emphasising a relaxation (or stimulation) in sensation or fantasy. Wilber confused readers by giving the impression that he was penetrating to the heart of Vedanta, Vajrayana Buddhism, and Zen Buddhism. This misleading "synthesis" became a dominant influence in so-called transpersonal psychology.

The relativism was confirmed at the end of the spectrum book. "The journey does not start Now, it ends Now, with whatever state of consciousness is present at this moment." (5) The acute subjectivism in this approach is glaringly obvious. Wilber adds: "That is the mystical state." Such a state would be one of useless delusion, too common amongst Western meditators.

Disappointing was the further exaltation of therapy evident in Wilber's No Boundary: Eastern and Western Approaches to Personal Growth (1979). Such books served to prop up the alternative therapy movement, which made rather casual genuflections to Eastern mysticism. "Gestalt therapy embodies an excellent and theoretically sound approach" (6) wrote Wilber enthusiastically. The diversions endorsed by Wilber created widespread confusion, to the financial gratification of predatory parties.

After recommending Transcendental Meditation (a joke to critics), Wilber commenced the final chapter of No Boundary entitled "The Ultimate State of Consciousness." Yet therapy intrudes even here, and what remains is very much in the idiom of an exhortation to live in the now instead of searching for truth. "To move away from now is to separate yourself from unity consciousness." (7) Some would rather be separate than to affirm with Wilber that "the works of Bubba Free John [Adi Da Samraj] are unsurpassed." (8) This American guru gained notoriety for a hedonistic lifestyle.

Zen Buddhism was another major influence on Ken Wilber's present-centredness. He approvingly quoted Suzuki Roshi's assertion: "The state of mind that exists when you sit (in zazen practice) is, itself, enlightenment." (9) The distinct tendency to be satisfied with formalities may well be perennial, but not necessarily proof of insight. Certainly, the shallow logic of "no path" became very popular in Californian Zen. According to Ken Wilber, "the true sages proclaim there is no path to the Absolute." (10) The names used in support of this categorical statement are Krishnamurti, Eckhart, Huang Po, and Shankara. Pathlessness is definitely true of Krishnamurti, and perhaps Eckhart. However, Shankara is misrepresented, his teaching not amounting to the popular American version. The Upanishads do state that there is a path. The identity of true sages remains to be confirmed in a historical context, as distinct from the deceptive lore of therapy and meditator convenience.

The concept of "no path" abetted the lucrative livelihood of many alternative therapists, who preferred to live in the gestaltist joys and revenues of the exploited present moment.

The spectrum model accumulated further distortions in The Atman Project (1980), a book that proved influential in what became known as transpersonal psychology. The sub-title was A Transpersonal View of Human Development. The American transpersonalists are sometimes said to have originated in humanistic psychology, associated with Abraham Maslow, who became famous in the 1960s. Transpersonalists understandably reacted to behaviourism and psychoanalysis, but introduced sweeping and simplistic perspectives believed to be of "spiritual" significance. The amorphous popular trend known as the Human Potential Movement was a background scene of confused ideation, the related "workshop" fashion providing a largely unrecognised form of exploitation and also a hazard.

Much in-crowd praise devolved upon The Atman Project. In particular, the appendix of various tables was treated by fans as an authoritative ready reckoner index to human development. The author said of these tables that he was "setting out all the various stages of various developmental schemas suggested by respectable researchers." (11) Those so-called researchers included the audacious American guru Adi Da Samraj (1939-2008).

Much of The Atman Project revolves around Western psychological theories. An improvised mythicist element is discernible. To such an extent indeed that the reader is treated to terms like the "uroboric self" and the "typhonic self." Nearly two thirds of the way through, the lower levels of the spectrum reappear pronouncedly in such sub-headings as "uroboric incest and castration." This atman project of Wilber psychology puzzled readers who have attempted to find out why The Atman Project was considered a classic of perennial philosophy by transpersonalists. The reason may be that the final chapter dwells upon the Tibetan Book of the Dead, a familiar landmark to the psychedelic generation influenced by Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert (Ram Dass).

The legend of The Atman Project as a guide to "perennial philosophy" may be attributed to over-enthusiastic transpersonalists. In the preface to that book, Wilber does not actually mention the subject of perenniality, instead expressing a concern to separate the "transpersonal realm" from the infantile. This exercise was again bounded by relativistic idioms. The same preface contained an assertion that the thesis "is finally a lie in the face of that Mystery which only alone is." (12)

5. Up from Eden Versus the Archaeology of Sumer

There is little doubt that Ken Wilber's next book Up from Eden (1981) comprised his version of the perennial philosophy, becoming widely advertised as such by the publishers. The sub-title was A Transpersonal View of Human Evolution. The book gained elaborate praise in transpersonal circles. However, Wilber's evolutionism is not easy to let pass without criticism if a more exacting context for history is desired.

An indication of the partisan evaluation is afforded by a comment of transpersonalist Stanislaf Grof. This therapy entrepreneur stated that Up from Eden "offered nothing less than a drastic reformulation of both history and anthropology." (13) A distinctive Wilberian vocabulary, e.g., the Typhon, was in evidence. Wilber located a fashionable "perennial philosophy" in the format bestowed by Coomaraswamy and Huxley.

In transpersonal anthropology (or sociology), Wilber elevated his two major ideological interests (Vajrayana and Zen) to a unique evolutionary status. American Buddhism thus gained transpersonal qualifications tending to glorify the roles of Chogyam Trungpa and Alan Watts, who are controversial elsewhere.

One of Wilber's leading supporters, Professor Roger Walsh, provided a summary of Up from Eden. Walsh claimed that Wilber integrated the evolutionary theories of Teilhard De Chardin, Jean Gebser, and Shri Aurobindo. Wilber argued that an altogether new category of spiritual consciousness emerged amongst humanity from about the sixth century CE onwards. This highly speculative theory elevated the Zen founder Bodhidharma and the Indian Vajrayanist Padmasambhava. All former mystical and religious traditions (not to mention philosophies) are here construed to have been inferior levels of evolution, including Indian sages like Gautama Buddha. The basic argument behind this gradation is Wilber's suggestion that, as various mystical states "emerge sequentially in today's contemplatives, they emerged sequentially in human history." (14)

This suggestion has a number of problems tending to evoke a duly critical reception. Wilber did not investigate or present enough of the extant facts and probabilistic data relating to the traditions "sequentially" demarcated in his theory. Despite the widely advertised role of Up from Eden as a commentary on the perennial philosophy, the internal contradictions within that popular scenario were not generally perceived or acknowledged.

A logical point to bear in mind is that, by admitting the sequential unfoldment of experience in today's contemplatives, Wilber unwittingly undermined the celebration of "now" that is still tiresomely proclaimed by the Alpert bandwagon. On this premise, the conclusion is inescapable that different contemplatives will apprehend the fabled perennial to very different degrees. In other words, what appears viable to some can appear as a deception to others. The sequential unfoldment of experience amounts to the neglected "path," entailing a vital onus to negotiate the static effects of a "now" imposed by the personality, whose habits extend to meditation and delusion.

In transpersonal evolutionism, Buddha and Jesus are less advanced than Padmasambhava, while all prehistoric shamans were less advanced than Lao-Tzu. The former two entities are more tangible than the latter two, though all are enveloped by legend. Lao-Tzu was the putative author of a famous Chinese manual of statecraft, often mistaken for a mystical text. His spiritual status is totally elusive. This very obscure entity "actually passes out of historical reckoning." (15) Accordingly, one has to negotiate the lore devised by American transpersonalism.

Wilber acknowledges a pervasive influence of the Hegelian model in his theory. That model is notoriously invested with a sense of European advancements superseding all former eras. In the Wilberian model, American transpersonalism similarly gains prestige, while relying upon the halo awarded to the presumed Zen-Vajrayana uniqueness. The available historical information on Bodhidharma and Padmasambhava is very slight, and quite insufficient to credit either of them with a greater status than Gautama.

The need for further caution arises when a bohemian guru like Adi Da Samraj (Da Free John) is considered an exemplar of the transpersonal advance. Wilber tends to present this antinomian figure as being on equal par with Ramana Maharshi, (16) one of the more compelling Hindu sages of the twentieth century. Ramana was not antinomian, a basic factor missing from the theory here disputed.

Ken Wilber commences Up from Eden with a quotation from Plotinus: "Mankind is poised midway between the gods and the beasts." What Wilber managed to make of this theme is very questionable. Wikipedia has more recently described Wilber as a neoplatonist, which seems a rather forced interpretation of his output. A neo-Gebserian is probably a more accurate classification. Wilber closely followed the format of Jean Gebser d.1973), who imposed upon cultural evolution a repetitive formula of archaic-magical-mythical-mental-integral. This straitjacket was borrowed by Wilber, who identified strongly with the integral association, denoting an advanced stage.

Several million years are treated by Wilber in an acutely deductive manner. The reductionism is sufficient to cast doubts on the transpersonal hypothesis, currently identified with "integral spirituality." Wilber claimed that his book contained "not just the perennial philosophy, and not just a developmental-logic, but a sociological theory based upon both." (17)

More soberly, and on the same page, Wilber honestly stated that there is "precious little detailed anthropology and archaeological data" in Up from Eden. That dearth leaves us with a wealth of citations from a limited number of sources, including the mythicist Joseph Campbell (18) and the evolutionary theorist Erich Neumann. The bibliography is too full of Freud and popular psychology, and far too sparing in historical sources supplied by specialist scholarship.

The "perennial philosophy" in this theory is really no older than the Coomaraswamy-Huxley-Huston Smith output. This "perennial" factor rests upon a basic set of assumptions, to which Gebserian formulae and other topical theories are added. For instance, the American psychologist Julian Jaynes (1920-97) is cited by Wilber as support for "the invention of history" at circa 1300 BC, which we are asked to believe is a part of the "lower egoic period" in human evolution. (19) According to Jaynes and Wilber, the only appreciable progress for the human race began at this era, with the transpersonalist being slightly more generous in allowing a rudimentary subjective consciousness prior to that.

The speculations of Wilber can read like a claim to omniscience. "Sometime during the first and second millenia B.C., the exclusive egoic structure of consciousness began to emerge from the ground unconscious." (20) Wilber also asserts that at this era, "evolution produced the first fully self-conscious beings." This declaration is accompanied by an assumption of "the scientific fall." We are told that mankind had formerly been "blissfully asleep in nature's subconsciousness."

The invention is elaborated in terms of a bizarre argument. This "scientific fall was a historical move up from the subconsciousness of Eden." (21) There is absolutely no history involved, only a Wilber speculation about the ego and the bicameral theory of Jaynes, the latter amounting to a misapplication of neuroscientific data about brain hemispheres.

Wilber was here confusing human history with his contempt for theological versions of Eden. This means that we are moving "up from Eden," not down from it, despite the accompanying assumption of a scientific fall. The American transpersonalist interprets Darwinian theory in terms of a supposed backwardness of all the numerous archaic human sociocultures. In this version of humanity, very little of conscious significance occurred between the apes and the "scientific fall." So much for short term perennialism in the cause of Zen and Vajrayana, traditions and lore that became popular in America during the late twentieth century. The realistic vintage is circa 1965, and no earlier.

The neo-Hegelian transpersonalist extrapolated the "Great Chain of Being" in terms of modern assumptions about primitives lacking self-conscious life, assumptions shared to some extent by Jean Gebser, Jung, and Neumann. Perhaps the radical Jesuit Teilhard De Chardin tried harder to break his mental conditioning. However, Teilhard is popular in the new age for his absurdly romantic theory of the Omega Point in evolution, in which all souls will reawaken to God consciousness.

The spectrum model of Wilber is applied to human evolution in a manner loaded against early civilisations. All archaic men were infants, is the message here, even if some of them may have gained a partial self-consciousness. Their abused myths and religious concepts receive little more credit than in Jaynesian bicameral speculations, which invoked auditory hallucinations as the basis for all religious insights. Generalisations about the "Great Mother" theme are today so ubiqitous that more specific observations would not stand a chance against popular reductionism.

Wilber effectively eschews most of the data and meaning relating to human evolution. He does fleetingly acknowledge the intuitions of Pyramid Texts, and awkwardly refers to "the profusion of brilliant metaphysical and spiritual insights" associated with ancient Egypt (Up from Eden, p. 108). However, a belittling theme is that archaic men banded together in secret societies, in order to escape the dominance of the feminine principle. The Great Mother meant human sacrifice, (22) suggests Wilber, who was relying upon superficial mythicist cues, despite the lack of evidence in numerous sociocultures not mentioned in Up from Eden.

Transpersonal theory was here strongly influenced by Joseph Campbell, whose version of mythology urged that the "Great Mother" format began to change circa 2500 BC into the male-oriented "Hero" myths. Wilber affirmed that "the true hero myths do not emerge before this period (c. 2500 B.C.) because there were no egos before this period" (Up from Eden, p. 184). The egoless archaic landscape is open to question. For instance, the Pyramid Texts are associated with the powerful Heliopolitan priesthood, active in the early third millenium. It is surely too much to believe that such priests and the mighty Pharaohs had no ego.

Another influence upon the "Great Mother mythology" of subconscious Eden was Erich Neumann (d.1960), a Jungian who surmised that the self at this archaic stage of evolution "was not yet strong enough to detach itself from the Great Mother, from mother nature, from the body, the emotions, and the flood of the unconscious." (23) The implication is that moderns are so much more liberated, which is not at all convincing in vew of the body-oriented permissive society we have today. A significant portion of the internet is devoted to pornography.

The adventures of Ken Wilber with the Oedipus myth of the Greeks are no more convincing than Freud's obsession with this confusing artefact, inherited in different versions from classical writers and dramatists. The Sphinx is a sexual symbol, urged Wilber. (24) Symbols can mean anything in contemporary psycho-lore. The blindness resulting from Freudian theory could easily be described in terms of a disastrous fall from scientific accuracy.

According to myth analyst Robert Graves, the Freudian theory of the "Oedipus complex" as an instinct common to all men, was suggested by a perverted anecdote of the Sphinx, one deduced by Greek fabulists from an icon showing the winged moon-goddess of Thebes. The remorseful self-blinding of Oedipus has been given an extreme interpretation by modern psychologists in terms of castration. The antique theme could merely have amounted to a theatrical detail later added to the original myth, whatever that was precisely. (25)

The reconstructed Ziggurat of Ur, site of an archaic city in Mesopotamia (Iraq) |

Comparatively hard data appears momentarily in Up from Eden speculations. Wilber here refers to Sir Leonard Woolley's excavation at the "Royal Tombs" of Ur, near the well known Ziggurat of Ur in Sumer (now Iraq). "Whole courts had been ceremonially interred alive." Wilber's description merits caution; there is no proof that entire courts were interred, the tomb contents elsewhere being described in terms of households. Moreover, details of the site in question have been debated amongst specialists; complexities are obvious. Further, that site does not exhaust the copious inventory of Mesopotamian archaeology, which goes back eight thousand years and more. All this is lost to view in transpersonalism. "We needn't dwell further on the historical details" says Wilber in the same myopic paragraph. He punctuates this closure on archaeology with the misleading reflection: "In a phrase, what we call civilisation, and what we call human sacrifice, came into being together." (26)

That abrupt excision of the details is altogether too convenient for stories about the gradual acceleration of the fledgling self-consciousness to Mahayana Buddhist glories. The beginning of civilisation is far more complex than Wilber envisaged. For one thing, collective burials are not generally attested at Sumerian sites, which have a history far older than the "Royal Tombs" of Ur. Sumerian civilisation of the third millenium BC is not accurately described in terms of human sacrifice. The extensive literature involved in Mesopotamian studies, plus related archives, permits a radically different perspective to that of transpersonalism or "integral psychology." The Wilber cause of integralism should be notorious for what is left out, not what is included.

Cities of Sumer. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons |

The Sumerian site at Ur is described by some commentators as the Royal Cemetery. This was in use for centuries from circa 2600 BC. The sixteen "royal graves" are dated to the period c. 2600 - c. 2500 BC. This phase of time is part of Early Dynastic III in more nationwide terms. In numerous other graves, a straightforward burial procedure occurred, the corpse being wrapped in matting or placed in a coffin. In the sixteen more imposing graves, a collective burial is attested. According to a well known interpretation, attendants willingly drugged themselves to a painless death (taking a cup of "poison"), including musicians and soldiers, although many were females. "Technically this was self-immolation rather than human sacrifice." (27) A relevant article of Leonard Woolley is available online (The Royal Tombs of Ur of the Chaldees, The Museum Journal XIX no. 1, 1928, 4-34). The mode of death is disputed.

Collective burial is attested on a smaller scale in other countries and in other eras, mainly featuring male servants, e.g., in First Dynasty Egypt, also amongst the Scythians and Mongols of a much later period. However, in Mesopotamia, only the Royal Cemetery at Ur was the known scene for such burials (an excavation theory about a cemetery at Kish has been strongly contradicted). A pressing conclusion is that royal burials with "human sacrifice" fell into disuse at a very early date. (28)

Some commentators refer to the "so-called Royal tombs" at Ur. Nearly 2,000 graves were excavated in the cemetery at Ur, but only sixteen of these qualified for the category of "royal." The absence of royal inscriptions has caused puzzlement. The lack of conclusive evidence led to a denial that these prominent tombs contained royal burials. Counter-theories were formulated, including a contention that the major participants were not royalty but representatives of a priesthood who participated in the annual "sacred marriage" rite. A variant suggestion has been that royalty were involved in the cultic sacred marriage. However, an objection to this theory is the lack of evidence for the sacred marriage rite having ended in death for any of the participants. A precise context for the collective burials is still unresolved.

Marble female head from Uruk, fourth milleniuium BC. Courtesy National Museum of Iraq. This head, discovered in the Eanna precinct, is almost life size, being 20 cm in height. The artefact is variously dated in the literature to circa 3500 BC and 3100 BC. The eyes and eyebrows would originally have been inlaid. Some writers suggest that this head represents the goddess Inanna, a theory for which there is no proof. |

A number of cities existed in Sumer by the late fourth millenium BC, each functioning as a temple centre, with a complex religion in formation. A high degree of craft specialisation was already present. Uruk and Kish served as nuclei in the first literate urban socioculture. Uruk achieved a city wall almost six miles long. (29) The transpersonal mythicist contraction, of such prominent archaeological data, may serve as a warning against mutated "perennial philosophy" lore. (30)

The Uruk period commenced circa 4000 BC, discernibly representing the origin of urban civilisation in the sense understood today. However, there are strong links with the preceding Ubaid period (fifth millenium BC), which is very imperfectly known. Ubaid was definitely the focus for an early temple culture of considerable interest; those events are remote from contemporary "Great Mother" speculation.

Dating for the Uruk period has long been in review. Calibration has revealed contradictions and uncertainties. Revised radiocarbon dating implies that several centuries may require adding to the initial commencing dateline of c.3500 BC. Excavation identified eleven major levels of occupation, some with substantial sub-periods, meaning that "a span of a thousand years does not seem ridiculous" (Crawford 2004:23). The period under discussion more realistically became 4,200-3000 BC. Even that revisionist format now appears to be outdated. Some scholars have favoured the dateline of 3200/3150 BC for the end of Late Uruk (Brisch 2013:114). This phase is now even defined in terms of circa 3500-3300 BC (Crusemann 2019).

The Anu Ziggurat at Uruk (Warka) in Iraq. Courtesy Essam Al Sudani/AFP

|

The Uruk site attests a lengthy sequence of cities built on top of each other. The Anu Ziggurat commenced circa 4,000 BC, subsequently undergoing many phases of construction, including a substantial staircase made of limestone blocks. The Anu, or Kullaba, precinct, dates back to the fifth millenium Ubaid era, when this settlement was already a town. "By around 3200 BC, the largest settlement in Southern Mesopotamia, if not the world, was Uruk: a true city dominated by monumental mud-brick buildings decorated with mosaics of painted clay cones embedded in the walls, and extraordinary works of art" (Uruk: The First City).

At circa 3500 BC, the second Uruk precinct of Eanna was creating "a unique complex of vast ceremonial buildings elaborately decorated with pilasters and cone mosaic" (Oates 1976:110). This site furnished the earliest known instance of the use of columns in a monumental building. The columns were over two metres in diameter. A celebrated cone mosaic court was part of the complex. Indeed, "hundreds of thousands of such [painted clay] cones were used in the adornment of a single building" (ibid:113). Two of the oldest Eanna temples are known as the Mosaic temple and the Limestone temple. The latter also has cone mosaic, the giant size being 76 by 30 metres (Crawford 1991:60). Monumental architecture was accompanied by the innovation of early writing.

The Uruk site expanded from 250 to to 500 hectares. Some commentators have duly stated that prehistoric Uruk was larger than Periclean Athens. "Settlement at [classical] Athens apparently covered some 200 hectares for a full three centuries" (Ian Morris, The Growth of Greek Cities in the first millenium BC, p.4).

The two Uruk settlements of Kullaba (Anu) and Eanna merged to form one community. Kullaba "centered around an important sanctuary dating back to the late Ubaid period" (Oates 1976:110). A city wall was eventually constructed circa 2900 BC, being almost six miles in length, "enclosing an area of some 3.5 square miles" (ibid). This is equivalent to 900 hectares, representing substantial urban growth. The population of that changing era is estimated at between 60,000 and 140,000. The Eanna buildings were destroyed, in obscure circumstances, at this approximate time. Other buildings were supplied instead. Ascertaining the nature of events has proved extremely difficult.

Some archaeologists refer to Uruk as being one of the largest cities of Sumer by 3000 BC. About 40,000 residents were already in Uruk by that time, a very large population for this archaic era. Uruk was a centre for "a multitude of technical innovations, including irrigation canals, plaster mortar, astronomy, writing, literacy and numeracy" (Jorg W. E. Fassbinder, Beneath the Euphrates Sediments: Magnetic Traces of the Mesopotamian Megacity Uruk-Warka, 2020).

A "priest king" of Uruk, alabaster statue, circa 3000 BC. Courtesy National Museum of Iraq. This bearded figure is apparently wearing a shepherd's hat, the crown of a Sumerian king. |

Uruk was “dominated by large temple estates whose need for accounting and disbursing of revenues led to the recording of economic data on clay tablets” (The Origins of Writing). Irrigation agriculture was the basis for prosperity. The prehistoric city was apparently ruled by an entity now often called a “priest king,” depicted in Uruk iconography over centuries. Those rulers are associated with a stratified society. Very little is reliably known about the evocative category. "This designation [priest king] is based exclusively on the iconography, which depicts the Uruk ruler as a priestly official, warrior, and hunter" (Steinkeller 2017:82).

German archaeologists dominated Uruk excavation from 1912. At Anu, they discovered a distinctive structure built largely underground. Measuring 25 by 30 metres, this exhibited an unusual labyrinthine plan surrounding a central space; the structure has been interpreted as serving a cultic purpose unknown today.

According to one calculation, the Limestone temple would have taken 1,400 workers some five years to complete. Large quantities of roofing timber must have been used, apparently acquired from the distant Taurus or Zagros mountains. Uruk was a project involving “staggering amounts of both labour and resources” (Algaze 2013:79).

Several thousand “Archaic texts” (proto-cuneiform) were excavated in Eanna IV-III levels. Mainly of economic relevance, many of these date to circa 3400 BC or earlier; a much older system of tokens was previously in favour. An important source comprises the fragments of a very early scribal text, the Titles and Professions List, dating to Uruk IV. A complete version dates to the subsequent Early Dynastic period, listing “over 120 categories of specialised administrators and priestly personnel in some sort of hierarchical order" (Algaze 2013:80).

The factor of slavery applies to Uruk. The Archaic texts include frequent reference to indentured labourers and foreign captives (male and female). One text reports 211 prisoners employed as labourers. “Most of the personal names we have for the earliest Mesopotamian cities and states are those of slaves rather than those of their owners” (ibid:81). In later centuries, some adjacent mountain peoples were viewed by Sumerians as primitive nomadic cattle raiders, apparently lending an excuse to obtain slaves from the mountains.

The much earlier Uruk slaves had non-Sumerian names, a factor explained by some analysts as a consequence of Empire extension. The issue is controversial. The Uruk culture apparently infiltrated Susa to the east, and also locales in Syria and Turkey. The Susiana plain of Khuzestan, in south-west Iran, was another home of early cuneiform writing, soon after the Uruk precedent. The extent of Uruk influence on Susa is in dispute.

Early proto-cuneiform clay tablet, probably from Uruk, c. 3100-2900 BC. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art |

A common belief is that recorded histories are the first sign of cultural progress. The insistence of Ken Wilber that historical records commenced circa 1300 BC is well down on the achievements of Sumerian scribes over a millenium earlier. At circa 3400 BC, a separate social class of scribes emerged to exercise their talents, the mode of writing gradually becoming more sophisticated and specialised. The initial Sumerian pictographic script is in strong evidence at Uruk, where large numbers of inscribed clay tablets were found, dating to the late fourth millenium BC. An early pictographic tablet from Kish is dated circa 3500 BC. Many early surviving cuneiform (and pictographic) tablets convey economic details. In addition, the record attests:

Historical and literary compositions began to appear, together with letters and dedicatory inscriptions of all sorts. These dedications provide us with some of the earliest historical texts we have. They record the names and deeds of some of the early kings of the Early Dynastic period.... There are also dictionaries and scientific and mathematical treatises used by the scribes in their capacity as surveyors and astronomers. (31)

The history of Sumer, from circa 2500 BC, gains profile from administrative documents and related sources. Much is known about rulers, political conflicts, and other matters during the last centuries of the third millenium BC. Earlier centuries are relatively sparse in detail. The administrative texts are "important sources for the study of socio-economic histories" (Brisch 2013:112). Wars, religious events, and building activities are included. However, as in other countries, the overall social picture is incomplete. "The textual evidence was part of the sphere of ancient elites," and accordingly, the format is "tenuous and biased" (ibid:113).

Kingdom of Ebla and Influence in the Mediterranean Levant. Courtesy Davius, Wikimedia Commons |

A significant extension of the Sumerian cuneiform heritage occurred at the city of Ebla in northern Syria. Nearly 20,000 cuneiform tablets (many of them in fragments) were discovered here in 1974-5. As a consequence, much is now known about Ebla that was formerly a blank. Ebla was first discovered in 1964, and subsequently described in terms of an early Syrian city state with Sumerian affinities. Previously, most scholars believed that archaic northern Syria was an arid semi-desert of no relevance, being inhabited only by nomads. The clay tablets date to the mid-third millenium BC, prior to the destruction of Ebla (probably by the Akkadians). Some texts were composed in Sumerian, while many others were written in a local Semitic language of Ebla. This cuneiform archive includes legal, executive, administrative, military, economic, lexical, and literary texts. One interpretation reads: "Ebla, unlike other Sumerian city states, was essentially a secular society, and a sharp distinction was maintained between political and religious life" (Greg Bradsher, The Royal Archives of Ebla, 2020).

Ken Wilber effectively dismissed the entire Sumerian (also Akkadian) heritage existing over many centuries. In contrast, a specialist scholar in America wrote that Western man seems unable and unwilling to understand such religions as the early Mesopotamian variety except from a distorting angle, employing simplistic yardsticks like nature worship, stellar mythologies, vegetation cycles, and pre-logical thought. (32) To this reductionist list should be added the straitjacket vista of "perennial philosophy," associated with the novelist Aldous Huxley and "I am Big Mind" fantasists like Ken Wilber. Perennial philosophy should read: preferential philosophy of retrospective codifiers. The history of religion is a very complex subject.

There are problems even in specialist literature on Mesopotamia. In 1999, Professor Marc Van De Mieroop referred to a recent paper in which the author demonstrated "unequivocally that modern views on ancient Mesopotamian urbanism reflect the intellectual biases and ideological stances of individual scholars and their times." In fact, even other papers in the same recent volume "demonstrate that colonial discourse survives in ancient Near Eastern studies two decades after the humanities and social sciences in general have subjected it to devastating critiques" (Van De Mieroop 1999, preface). More specifically, the critic was here resisting "the Eurocentric teleology of history that sees Greece as the birthplace of 'our' civilisation" (ibid). Athenian society became the European ideal, engendering some inflexible conceptions.

Depiction of Puabi (circa 2600 BC) with jewellery discovered in the Ur cemetery |

The Sumerian civilisation is worthy of more attention than Wilber extended. The Sumerian culture created city states, each with an independent ruler. Although this was a male-dominated society, women could gain power and prominence. A well known image of Puabi (Shubad) is an evocative reminder. Her remains, together with a gold head-dress and ear-rings, were discovered by Woolley in the "Royal Cemetery" at Ur. The status of Puabi is disputed, linguistic factors being ambivalent in terms of a queen or a priestess.

Another well known entity is Enheduanna of Ur (born circa 2300 BC), a high priestess of the goddess Inanna. This woman, the earliest named poet, was a "daughter of Sargon," meaning the ambitious Semitic ruler of Akkad who gained control over Sumer via numerous military campaigns (the description of daughter has not been interpreted literally by all commentators). The hymns in her name are not unanimously regarded as authentic, a strong doubt existing in view of the late manuscript sources dating to the second millenium BC.

The name Enheduanna includes the title of en, meaning the leader of a temple community. That title appears in Uruk IV texts of the late fourth millenium BC, with the apparent primary meaning of an administrator responsible for the economic wellbeing of a local population. A thousand years later, the temple situation had apparently altered, cult ritual being more central and elaborate. Enheduanna is believed to have reconciled Akkadian theology with the Ur pantheon. In this process, of an evident political complexion, she was temporarily exiled by a Sumerian rebel determined to overthrow Akkadian rule at Ur.

A famous limestone disc, plus other material, confirm that Enheduanna "was installed as the cultic 'bride' (entum) of the moon god, Nanna, at Ur" (Kuhrt 1995:50). This role now increased in importance, with the officiant, "for the next 500-600 years, always being the daughter of whichever Mesopotamian king, who held (or claimed to hold) a power greatly superior to that of a mere city-ruler" (ibid). A manipulation of status is evident. "Enheduanna's prime duties were to pray for the wellbeing of the king, her father" (ibid). The Sargonid Empire soon stretched from North Syria to West Iran, a development attended by extensive temple construction as a means of social control.

l to r: The "Mask of Sargon," Akkadian period, possibly representing Naram-Sin, found at Nineveh in 1931, courtesy National Museum of Iraq. Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, detail, courtesy Wikimedia Commons |

Military organisation increased under Sargon and his successor Naram-Sin (rgd c.2254-2218 BC), the latter (Sargon's grandson) claiming divine status as the "God of Akkad," being depicted as taller than anyone else (with a horned helmet to signify his godhood). "Booty from his far-flung campaigns flowed into the king's treasury and was redistributed in the form of magnificant presents to temples, favoured subjects and members of the royal family - serving to stress the ruler's preeminent position, since he both created and controlled this wealth through his military exploits" (Kuhrt 1995:55). The Sumerian language eventually died out in competition with the Akkadian tongue.

This situation occurred in the wake of other frictions between city states of Sumer during the third millenium BC. A military strategy was adopted by Lagash, one of the oldest cities in Sumer, led by an ensi or governor in liaison with the priesthood. The high priests of Lagash were very influential, deciding who should reign. Lagash annexed much Sumerian territory. This period was marked by an increasing exploitation on the part of a wealthy class. The king (lugal) may originally have been elected by an assembly as a temporary war leader, this situation developing into a more permanent arrangement when city states grew more ambitious.

Slavery was another problem existing in the third millenium BC. However, references to "gangs of labourers" are considered ambiguous (Kuhrt 1995:39). Far less equivocal is the report: "The pre-eminent position of men over women was guaranteed by the king, who ordered that a woman guilty of speaking disrespectfully to a man shall have her mouth crushed with a baked brick; the brick was to be displayed at the city gate" (ibid).

A Queen of Lagash was Baranamtarra. In 2384 BC she and her husband Lugalanda (son of a high priest) gained the leadership of Lagash, becoming the largest landholders in the city. Baranamtarra presided over a temple and several estates. She managed her own private estates while conducting private business activites, which included the purchase and sale of slaves. Lagash was now prospering from international trade. Within less than a decade, Baranamtarra and her consort were overthrown by Urukagina. Lugalanda is described in the archaic records as being corrupt, confiscating local land. Urakagina "found the common people of Lagash suffering from the greed of their own officials." He undertook reforms, ousting the old bureaucracy, and establishing the amargi ("freedom") of citizens from exploitation (Finegan 2019:43). However, Urakagina could not withstand the violent rebound from conservative power, being invaded by Lugalzagesi of Umma, who burned the temples of Lagash.

Lugalanda assumed control over the most important temples in Lagash, appointing himself and his relatives as administrators. These temples were now his private property. His regime conscripted workers to labour in the royal fields. Temple officials are also described as being corrupt, charging high fees to perform religious rites and to bury the dead. Taking bribes, these priests exerted heavy taxes which they shared with the ensi Lugalanda.

The new ensi Urakagina claimed to represent the oppressed boatmen, farmers, shepherds, and fishermen. Boats, orchards, sheep, and fish stores had been confiscated by the tyrant Lugalanda. Urakagina now dismissed many corrupt officials, including those who controlled the grain tax. He imposed restrictions on the amount that priests could charge for their services. Urakagina also cancelled the evil of debt slavery, and dispensed charity for the poor and elderly. These reforms were recorded on his “liberty cones,” described as “the world’s first documented effort to establish the basic legal rights of citizens” (Urakagina, the reformist king).

Urakagina was not the first Sumerian ruler to attempt reform, but his effort was more comprehensive than anything else known. He has been diversely interpreted as the leader of a popular revolution, and as the upholder of the divine right of kings. He claimed inspiration from the gods, and was not an iconoclast. He changed his title from ensi to the more prestigious lugal, meaning king. He alienated the aristocracy and priesthood with his reforms. This development would not have assisted his subsequent defence of Lagash against the ruthless invader from Umma. He may have lacked effective military support. The attack on Lagash was ferocious, the looting of temples causing shock in a society of this type. Urakagina moved to the neighbouring city of Girsu, where he was again besieged, subsequently disappearing from the record.

A pressing issue is that of Sumerian kings instigating slave raids in the hills or mountains. To justify this practice, monarchs boasted that the gods had given them victory over an inferior people. One interpretation urges that Lagash was a city growing rich through slavery, kidnapping and selling the victims obtained in mountain country to the east. The Sumerians viewed the inhabitants of that mountain zone as hostile barbarian tribes. "The Sumerian ideograms for slave and slave-woman were originally pictograms composed of the signs Man+Mountain and Woman+Mountain respectively" (Westerbrook 1995:1641). This association has suggested that in very early times, meaning the fourth millenium BC, Sumerians may have raided the mountain country for slaves.

According to some scholars, slaves were imported and exported by private merchants in Sumer. Traders dealing in wheat, cattle, and property could easily add slaves to their agenda. Other Near Eastern civilisations likewise became dependent on slaves for agriculture, manufacturing, and wealthy households. Some commentators deduce that the Greeks derived their practice of slavery from the Near East. In Iraq, or Mesopotamia (a Greek term), the slave population included prisoners of war and the descendants of various subordinate categories. Slaves (or labourers) were used to build elaborate fortifications and temples.

Some interpretations tend to minimise the number of slaves until the end of the third millenium, meaning the Third Dynasty of Ur (Ur III). This period is revealed in a substantial number of sources, primarily administrative reports. "Chattel slaves appear regularly in the sale documents: it is estimated that about two-fifths of their number were indigenous - poor families selling their children, indigent family groups (such as mothers with suckling babes), or even sons selling their mothers in times of stress. Slaves themselves could amass property and eventually redeem themselves" (Kuhrt 1995:62).

Slaves in Sumer and Akkad often came from the depressed native population, for instance, debtors. There were also unemployed men and women who sold themselves into slavery. A slave woman could be sold with her children. During the Ur III period (2100-2000 BC), children were apparently employed at full capacity by the age of five or six, gaining only reduced rations. Children were often employed in connection with the textile industry. Details of an earlier temple construction project, of the Lagash II period (c.2260-2110), indicate that children could be worked alongside their mothers; beatings were commonly associated with such projects (John N. Reid, Children of slaves in early Mesopotamian laws and edicts, 2017).

Standard of Ur, circa 2500 BC. Courtesy British Museum |

An insight is afforded by the so-called Standard of Ur. Found in the Ur cemetery, this mosaic reveals naked prisoners of war being marched before a general (or king) of Ur, who is attended by soldiers carrying weapons. A cart, or proto-chariot, is also depicted in the same top horizontal panel. Attacking carts feature in the bottom panel. The wheel became a major aid to warfare. In this martial environment, assisted by cult ritualism, retainer sacrifice would not have been difficult to implement by elite factions, whether or not the victims voluntarily drank poison. Soldiers, servants, musicians, and priestesses were dispensable in the service of a very wealthy upper class.

Another revealing artefact is the Lagash Vulture Stele of circa 2450 BC. This shows decapitated heads of enemy soldiers from Umma carried off by vultures. The sculpture has been described by experts in terms of a fear tactic to deter enemies of Lagash. The civil war between Umma and Lagash lasted for generations. Lagash created an Empire, which became overstretched, falling to other ambitious rulers. The vicious circle of aristocratic greed and violence eventually destroyed Sumer, accompanied by ecological problems that vast wealth could not repair or prevent. A drought created famine; without rain, the salt content of soil increased, causing a reduction in crops. The price of grain became exorbitant. The invading Martu (Amorites), a nomadic people from Syria, were only one of the factors contributing to the downfall of Ur at the end of the third millenium BC.

The downward arc (not Up from Eden) was inherited by Babylon, where slavery continued in favour and savage punishments could be applied to criminals and slaves. Severed feet, cut noses, blinding, ripping out the heart, these were the draconian rules of justice. Even further down the chronological scale, the Assyrian Empire pushed cruelty to an extreme, proudly torturing slaves and prisoners of war while invading and destroying.

Moving back upwards to Mesopotamian Eden, Eridu generally represents the beginning of Sumerian cities. Here in southern Sumer, a temple settlement was apparently commenced during the sixth millenium BC, thereafter being occupied until c.600 BC. Mud brick temples were a basic feature of this early site, typically featuring diverse layers of occupation. Today located in a desert, Eridu once benefited from the marshland of southern Iraq. This settlement was gradually abandoned in the late fourth millenium, probably because of a rapid dessication of the surrounding plain. During the third millenium BC, Eridu recovered to become an important urban centre (Rebuilding Eden: In the Land of Eridu).

Kish ruins at the time of excavation in 1932. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons |

The most important city in northern Sumer was Kish, occupied from at least as early as 3200 BC, and counted as one of the twelve city states of Sumer. Kish is now a sprawling 24 square kilometre site featuring forty mounds and an eroded Ziggurat. British and American teams conducted excavation at Kish in the 1920s; no excavation has since occurred. Sand dunes and modern development are some of the drawbacks. A final report only exists for one of the six major areas of excavation. Roger Moorey, of the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford), composed an important account entitled Kish Excavations 1923-33 (Oxford 1978, also online). He emphasised that the word Kish is " a short-hand description for many closely related settlements extending back in time long before the rise of writing."

Subsequently, the British Museum complained that Kish archaeology was badly damaged by the American military presence in that region. In popular American new age lore, the city state of Kish is consigned to oblivion by mythicist calculations and Wilber "integral" theory. Human sacrifice commenced with the start of Sumerian civilisation; that is all we need to know in Up from Eden speculation. Iraqi sources have disclosed the existence of about 10,000 archaeological sites in Iraq, only a very small percentage of these having been excavated.

Ziggurat of Enlil, Nippur |

Despite the presence at Uruk of a large ceremonial complex in the late fourth millenium BC, that city was apparently not the major religious centre of Sumer. Later tradition attributes a dominant religious status to Nippur. Certainly, a large percentage of all known Sumerian literary works were discovered at Nippur. Scribal activity was intensive here. Over 30,000 cuneiform tablets come from this city, relating to history, economics, and literature (including parts of the Gilgamesh Epic). More than a hundred temples existed at Nippur, a city well to the north of Uruk and Ur. A lengthy sequence of mudbrick Inanna temples emerged on some sites involved. Nippur is now a mound sixty feet high and nearly a mile wide.

Nippur settlement commenced in the Ubaid period circa 5000 BC. This sacred city survived numerous wars and dynastic downfalls. A famous landmark is now Ekur, the Ziggurat of the god Enlil, chief deity of the Sumerian pantheon. Situated in the centre of an agricultural zone, the Nippur temples owned much land. Those temples produced their own goods (notably textiles). Some commentators describe such temples in terms of social welfare centres, catering for widows, orphans, and prisoners of war who worked in agricultural settlements belonging to a temple. In benign assessments of Sumer, the POW category was not necessarily that of a slave. The context of slavery appears to have become much more oppressive by the end of the third millenium BC. The democratic dimension of Sumerian society was seriously afflicted with the passing of centuries. Down from Eden was a miserable plight for vast numbers of slaves in the Babylonian, Assyrian, Greek, Roman, Arab, Turkish, British, and American sociocultures.

Moving back up earlier than Ubaid, the neolithic site of Chatal Huyuk is evocative. Located in southern Anatolia, this proto-urban settlement flourished for many centuries from 7000 BC. The population statistics were in comfortable terms of up to 8,000, much less than Uruk. The inhabitants built distinctive houses of a common design, with nothing unduly ostentatious. They had a capable sense of hygiene, burning and burying their garbage. Forensic tests have revealed a healthy population. There were no monumental buildings, a fact suggesting a very egalitarian society, at least in the earlier phases. Men and women apparently had an equal social standing. Some inhabitants engaged in long distance trade, a factor which may have eventually disturbed the balance.

This relaxed environment was later to be superseded by large surfeit populations, monumental architecture, the rise of acute class distinctions, predatory monarchies, excess wealth, wars between city states, slavery, urban squalor, and ultimately modernity, which now threatens planetary wellbeing to an unprecedented extent. Sumerian Ur and similar societies were hit by ecological setbacks, which were not enough to fatally disrupt the axis of planetary ecology. Today, elite billionaires play dice with vast populations in fragile urban environments, whose inmates are generally reluctant to part with their dangerous technology. Up from Eden is a precarious strategy, accompanied by the big profits in "human potential," a much advertised factor abused by entrepreneurs.

6. Transpersonal Assumptions and Deceptions

Moving into a further round of Up from Eden transpersonal theory, Wilber says that the first great sages emerged about the sixth century BC., "but rarely, if ever, before." The diminished sequence moves very fast in a pronouncedly preferential schema. Hinayana, the early monastic form of Buddhism, is unpopular in America, so this is accordingly low in rating. Wilber soon asserts that Zen Buddhism, "with the possible exception of its cousin Vajrayana, has historically produced the greatest number of enlightened practitioners, East or West." (33) Historical evidence for this contention is not supplied. The unversed reader might imagine that Chinese Ch'an (Zen) had never known reverses.

In contrast, specialist scholarship has indicated serious confusions in the early centuries of Zen; minority repertories associated with Ch'an monasteries underwent significant alterations when the originally small Ch'an movement expanded. (34) All that Ken Wilber briefly mentions, about deficiencies in the glorified traditions, is the American "Dharma Bum" period of the 1960s. At that time, persons claiming to pursue Zen ideals demonstrated a very lax attitude of narcissism. (35)

The contemporary scene is also glorified by Up from Eden preferences. "A handful of true gurus and real spiritual masters are making their influence felt," asserts Wilber, who was here clearly including Adi Da Samraj in the honours, and by implication, Chogyam Trungpa (d.1987). The latter is included in Wilber's bibliography; Trungpa's books were earlier recommended by Wilber. (36) Trungpa used the "crazy wisdom" he derived from Vajrayana as a virtual excuse for reckless behaviour; his behavioural lapses became notorious.

Wilber says enthusiastically that "legitimate centers of disciplined meditation are rapidly spreading" (Up from Eden, p. 324). Such reassurances may have been treated as a cover by Abbot Richard Baker and others who revived in American guise some old Mahayana lapses into antinomian lifestyles. The high degree of discipline exhibited by the traditional Japanese monk has often been lacking in American environments. The inverse example set by the British-born Alan Watts (1915-1973) proved persistent. The latter was a therapist, Zen enthusiast, and LSD experimenter who died of alcohol poison.

Moving from Britain, Alan Watts became celebrated in California during the 1960s. His books became popular amongst hippies and others. In his Psychotherapy East and West (1961), Watts urged that Buddhism can be regarded as a form of psychotherapy rather than a religion. His interest in Zen was regarded by critics as a flirtation. The eloquent lectures of Alan Watts gained many fans. One of his exhortations was to relinquish attempts at self-development, and instead simply "be yourself." In his private life, this orientation did not work. He tended strongly to a hedonistic attitude, being regarded by some as an exemplar of free love. Watts contracted a series of marriages in which infidelity and neglect of children were too obvious. Indeed, he gained a reputation for creating problems wherever he went. The hedonistic now was disastrous for him and others. (37)

In 1983, news spread that the San Francisco Zen Centre had problems. Abbot Baker, renowned as a roshi (Zen master), resigned the following year in circumstances of scandal over his personal conduct. There were also scandals concerning other "Zen masters" living in various American cities. Like Alan Watts, Abbot Baker favoured therapy, more especially "bodywork," which he thought produced similar effects to Zen meditation. In his milieu, meditation amounted to a number of sexual affairs with his pupils; Baker was also implicated in authoritarian abuse and financial misconduct. (38)

Zen proved to be one of the strongest "prerational" influences in American counterculture. In this context, Zen should be considered "archaic-magical-mythical," a derogatory Gebserian label aimed by Wilber at innumerable archaic traditions which are relegated to lesser evolutionary status in Up from Eden. Zen psychotherapy emerged amongst supporters of Californian Zen influenced by Alan Watts, who was believed to be an expert on satori (enlightenment). In his wake, Oscar Ichazo was able to use the concept of satori via Arica commune license occurring in Chile, another example of a confused host environment assimilating foreign ideas in an erratic manner. The "pathless" concept of satori is so open-ended as to mean almost anything outside a disciplined Japanese monastery, where moral rules are assumed to be mandatory from the outset.

The eighth century figures of Padmasambhava and Hui-Neng are credited by Wilber with "the first true and complete understanding of the Svabhavikakaya" or ultimate consciousness, which is said to be again "peaking with certain modern day sages, especially Sri Ramana Maharshi, Bubba Free John, perhaps Aurobindo" (Up from Eden, p. 320). In other words, Up from Eden process results in the antinomian excesses of Adi Da Samraj.

The supposed value of the "rational" in Wilber's integralism is anomalous when closely analysed (the transrational was evidently preferred). The element of rationality, in the Up from Eden evolutionary sequence, is consistently belittled. The "scientific fall" was purportedly attended by an increase of guilt. This theme links with emphases of alternative therapy. Wilber envisages the establishment of "centauric societies" during the next century "if all goes well" (ibid:325) This decodes in plain English to psychotherapy, or the supposed integration of mind and body, a commercial theme of the Human Potential Movement. Wilber indulges in the standard "humanistic" talk about repression (scarcely existing in Anglo-Saxon countries), and even a muted endorsement of Wilhelm Reich's theory of unrepressed emotions. (39)

One of the "centauric societies" is evidently the Integral Institute, since founded by Wilber in America. This organisation advocates Integral Life Practice, a drawback incorporating such new age favourites as Zen, Gestalt Therapy, TM, Yoga, Tantra, the Kama Sutra, Kundalini Yoga, Integral Sexual Yoga, and Big Mind Meditation. (40) Up from Eden means Down to Exploitive Modules, a "workshop" fashion afflicting gullible new age consumers.

In another direction, Wilber informs that Hegel's shadow "falls on every page" of Up from Eden. Wilber eulogises Georg W. F. Hegel quite pronouncedly. "None combined transcendental insight with mental genius in a way comparable to Hegel" (Up from Eden, p. 314). Hegel was confused by Wilber with the perennial philosophy, a phrase decoding to an elusive subject masked by conveniences of romantic commentators.

Hegel's philosophy of history revolved around the concept of a progressive development or actualisation of Spirit within human cultures. Very briefly, the development of Spirit was charted by Hegel as something deficient amongst the Orientals (Chinese, Indians, and others), and rather more advanced amongst the Greeks and Romans; the honours passed victoriously to the Germans of the Enlightenment era. Eastern peoples fared badly in this version of Spirit. They were considered to be the bottom end of evolution.

Hegel's Lectures on the Philosophy of History are attended by different editions in German and various English translations. These require some flexibility in coverage. According to the well known Sibree version, Hegel was resistant to the British esteem for Indian philosophy, and disapproved of the suggestion that Indian thought was superior to Greek philosophy. He found a moral deficiency in both China and India, while emphasising that India had not cultivated a due sense of history.

"Deceit and cunning are the fundamental characteristics of the Hindu," (41) asserted the transcendentalist. Hegel's account of India can read like the Christian missionaries of his day. Hindus were further castigated as possessing "a monstrous, irrational imagination," (42) a theme which might fit Wilber aspersions concerning early Asiatic civilisations. More pointed is the very misleading accusation: "Cheating, stealing, robbing, murdering are with him [the Hindu] habitual." (43)

Wilber is not dissimilar to Hegel in the reluctance to concede value to Islamic civilisation. In his professorial lectures delivered at Berlin during the 1820s, Hegel mentioned Islamic philosophy in a limiting format; he acknowledged the revival of arts and sciences during the early Islamic era, while viewing these developments as being peripheral to events in the German world. (44) In the Haldane translation, Hegel affirms that Islamic philosophers "established no principle of self-conscious reason that was truly higher, and thus they brought philosophy no further."

Hegel apparently wanted to be thought of as a Christian philosopher of the Enlightenment. He affirmed to the end his Lutheran identity. "The unity of divine and human nature is made manifest in Christ." (45) Christian monasticism was deemed false, an attitude reflecting a Protestant bias. The Indian concept of renunciation was also depreciated in terms of "the extinction of consciousness and the suspension of spiritual and even physical life." (46)

In contrast, Ken Wilber is an advocate of "integral spirituality." This ideology similarly signifies an acute reductionism in relation to global history. Wilber stated that no account of evolution can succeed in "an explanatory fashion without reference to what Hegel called the 'Phenomenology of Spirit.' " (47) However, it is fortunately possible to bypass the phenomenology, and also to perceive that "Up from Eden" theories rely for their argument upon misrepresenting and contracting the achievements of earlier sociocultures and minority repertories. (48)

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

August 2013 (modified June 2021)

(1) Ken Wilber, The Spectrum of Consciousness (Wheaton, Illinois: Theosophical Publishing House, 1977), p. 271, citing C. G. Jung, Analytical Psychology: Its Theory and Practice (New York, 1968), p. 110. The quotation from Jung also appears in Wilber, "Psychologia Perennis: The Spectrum of Consciousness" (74-86) in R. N. Walsh and F. Vaughan, eds., Beyond Ego (Los Angeles: J. P. Tarcher, 1980), p. 82. Wilber here described the transpersonal level in terms of Transpersonal Band therapy, an indication of the persistent confusion between therapy and other subjects.

(2) Wilber, The Spectrum of Consciousness, p. 11.

(3) Ibid:298. Wilber's spectrum model applies a superficial present-centredness to Mind. This tends to compromise the equation made between the physicist Erwin Schrodinger and Shankara. According to Wilber, both of these entities experienced Mind (ibid:260). Others consider this association to be very loose. A strong interest in Vedanta does not amount to ultimate experiences, howsoever these are defined.

(4) Radha Rajagopal Sloss, Lives in the Shadow with J. Krishnamurti (London: Bloomsbury, 1991), p. 200. The strong allegation emerged that for nearly thirty years, Jiddu Krishnamurti was the secret lover of one of his assistants, during which period he was party to three abortions in this relationship. These events occurred despite the fact that Krishnamurti encouraged his public image of chastity. Earlier, he had reacted to the absurdly theatrical "initiatory Path" taught by the Theosophical Society. For four decades from 1947, he travelled the world as a spiritual teacher, giving many public talks, and enjoying many luxury holidays. Krishnamurti acquired fine houses and fast cars, while encouraging the attention of admirers, who regarded him as a great saint. The "now" was a conveniently simplified doctrine. In lamenting the absence of a "path," some critics do not mean the Theosophical version of "path," but a more philosophical (or even spiritual) route past obstructions and conveniences.

(5) Wilber, The Spectrum of Consciousness, p. 338.

(6) Wilber, No Boundary: Eastern and Western Approaches to Personal Growth (Los Angeles: Centre Publications, 1979), p. 120.

(9) Ibid:144. The late Suzuki Roshi (S. Suzuki) is not to be confused with Professor D. T. Suzuki (1870-1966). The latter was also regarded as a Roshi (Zen master). Suzuki Roshi's book Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind (New York: Weatherhill, 1970) was described by Wilber as "a masterpiece" (No Boundary, p. 159). This book was very popular in American Zen.

(11) Wilber, The Atman Project: A Transpersonal View of Human Development (Wheaton, Illinois: Theosophical Publishing House, 1980), p. 177.

(13) Stanislav Grof, Beyond the Brain: Birth, Death, and Transcendence in Psychotherapy (State University of New York Press, 1985), p. 135. This book is controversial for the elevation of LSD psychotherapy.

(14) Roger N. Walsh, The Spirit of Shamanism (Los Angeles: J. P. Tarcher, 1990), p. 245.

(15) Shepherd, Some Philosophical Critiques and Appraisals (Dorchester: Citizen Initiative, 2004), p. 134. The Tao te Ching or Lao-tzu became part of Taoist tradition, which is not straightforward to comprehend. "The Taoist school, like all the others except the Confucian and Mohist, is a retrospective creation, and the most confusing of them all." The quote is from A. C. Graham, Disputers of the Tao (La Salle, Illinois: Open Court, 1989), p. 170.

(16) Wilber, Up from Eden: A Transpersonal View of Human Evolution (New York: Doubleday, 1981), p. 320. In a slightly later book, Wilber expressed lavish praise of Bubba Da Free John, whom he described as a spiritual adept and an authority on Yoga and kundalini. See Wilber, A Sociable God (New York: New Press, 1983), pp. 27, 29. Only two years after A Sociable God was published, Californian newspapers gave due coverage to a five million dollar lawsuit brought against Da Free John by a female devotee who alleged serious abuse of a sexual nature. Da Free John (Adi Da Samraj) gained over a thousand devotees, a fair number of whom are said to have read Wilber's books elevating their figurehead. Wilber is well known for a continuing estimation of this controversial guru.

(17) Wilber, Up from Eden, p. xi.

(18) Extensive reference is made to Joseph Campbell, The Masks of God (4 vols, New York, 1959-68). These volumes cover much world mythology, with an interpretation that is in dispute.

(19) Wilber, Up from Eden, p. 203, citing J. Jaynes, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind (Boston, 1976). Jaynes was an anthropologist at Princeton University. His idiosyncratic theory influenced the popular writer Colin Wilson, who caused further confusions about brain function and ancient history. See Shepherd, Minds and Sociocultures Vol. One, pp. 47-8, describing the Jaynesian thesis in terms of "one of the more misleading works in anthropology." Jaynes suggested that "the anterior commissures (much smaller than the corpus callosum) between the temporal lobes of the cortex provided the neural bridge which, with the aid of the articulatory qualities of the hallucination, built civilisations and founded religions" (ibid:48). Jaynes supplied a limiting interpretation of second millenium BC Mesopotamian inscriptions and tablets. Wilber was dogmatic in asserting that "the earliest form of history is dated c. 1300 BC" (Up from Eden, p. 203). In reality, there are historical documents (if sparse in nature, also tending to mythology) extant from third millenium BC Sumer. Early administrative documents reveal much about social life. For a long time, literary texts of that era went unrecognised even by specialists. These texts are not economic in content, and date back to circa 2,600 BC or perhaps earlier. They include religious genres such as hymns and myths, and non-religious genres such as proverb collections and lexical texts. Although part of this corpus was discovered at Tell Abu Salabikh, the complement of cuneiform tablets from Fara was published much earlier in 1923 and neglected for nearly half a century. The literary texts indicate a highly developed Sumerian scribal tradition which must have commenced long before. See, e.g., R. D. Biggs, "An Archaic Sumerian Version of the Kesh Temple Hymn from Tell Abu Salabikh," Zeitschrift fur Assyriologie (Berlin 1971) 61: 193-209; Biggs, Inscriptions from Tell Abu Salabikh (Oriental Institute of Chicago, 1974); B. Alster, "On the Earliest Sumerian Literary Tradition," Journal of Cuneifrom Studies (1976) 28: 109-26.

(20) This quote was included in Frank Visser, Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (State University of New York Press, 2003), p. 100, citing Up from Eden, p. 179. The Visser coverage was partisan, an angle which subsequently changed after Visser encountered drawbacks in the approach of Wilber. Frank Visser became a leading critic of his subject, maintaining a website including critical analysis of Ken Wilber.

(23) Ibid:130, drawing upon E. Neumann, The Origins and History of Consciousness (Princeton University Press, 1973).

(24) Up from Eden, pp. 240, 42. Wilber admits that Freud "overstated the case" (p. 238) in his formulation of the neurotic Oedipus complex. He nevertheless asserts that Freud's thesis is "central to any comprehensive theory of human compound nature" (p. 240). In contrast, I take the view that a comprehensive theory renders the view of Freud peripheral. According to Wilber, the Oedipus legend is "the myth of consciousness torn between the old chthonic matriarchate and the rising solar patriarchate" (p. 238). This theory has the acute disadvantage of viewing the entire phase of "chthonic matriarchate" in terms of "emotional-sexual intercourse" and "seeking unity via the body" (p. 239).

(25) Robert Graves, The Greek Myths Vol. 2 (revised edn, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1960), pp. 13-14. Professor Graves notably derided Jungian interpretations of myths as "original revelations of the pre-conscious psyche, involuntary statements about unconscious psychic happenings" (The Greek Myths Vol. 1, revised edn 1960, pp. 21-2). Graves believed that "a true science of myth" should commence with a study of archaeology, history, and comparative religion (ibid:21). The tendency to simplification elsewhere has often been astonishing.

(26) Up from Eden, p. 127. The reductionist nature of "integral" theory is obvious at a glance to informed parties. In Up from Eden, Wilber ignored such books as the relatively well known work which supplied a summary of some complexities applying to the "Royal Tombs" of Ur. See Henry W. F. Saggs, The Greatness That Was Babylon (London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1962), pp. 372ff. "That the 'royal' tombs of the First Dynasty of Ur represent the culmination of the Sacred Marriage seems to the present writer the best explanation of the facts" (ibid:381). This despite "a few residual difficulties" in the explanation provided by Moortgat. Cf. A. Moortgat, Tammuz (Berlin: Gruyter, 1949). In another direction, a relevant detail is that "some scholars, basically accepting Woolley's theory of a human sacrifice, have been so struck by the oddness of it in Sumer that they have been driven to postulate a foreign invasion by some race (possibly the ancestors of the Scythians) amongst whom such barbarities are known (at a later period) to have taken place" (Saggs, op. cit., p. 380). The discoveries of Sir Leonard Woolley are documented in, e.g., Woolley, Ur Excavations Vol. 2: The Royal Cemetery (London: British Museum, 1934); P. R. S. Moorey, Ur of the Chaldees: A revised and updated edition of Sir Leonard Woolley's Excavations at Ur (London, 1982). See also Moorey, "What do we know about the people buried in the Royal Cemetery?" Expedition (1977) 20: 24-40.

(27) Henry W. F. Saggs, Babylonians (London: British Museum Press, 1995), p. 65, stating that none of the bodies showed any sign of violence or disorder. The collective burials varied from three to seventy-four corpses. Cf. Aubrey Baadsgaard et al, "Bludgeoned, Burned, and Beautified: Re-evaluating Mortuary Practices in the Royal Cemetery of Ur" (125-158) in Anne Porter and Glenn M. Schwarz, ed., Sacred Killing: The Archaeology of Sacrifice in the Ancient Near East (Winona Lake, IL: Eisenbrauns, 2012). This article emphasises the severely decayed state of the tomb skeletons, a fact making the exact cause of death difficult to determine. Information is supplied that CT scans show signs of blunt force used on at least one of the sacrificial victims. Cf. Raquel Belden, Royal Tombs at Ur Research Project (Trinity University Award, 2019, online), reviewing a number of interpretations about the sacrifices. There is no direct support for Moorey's theory of priests and priestesses being ritually sacrificed. There is likewise no support for a theory of substitute royals being slaughtered (ibid). Strangulation has also been suggested. Many of the tomb retinue were women, a factor evoking a theory that these women were priestesses of the moon god Nanna. Belden concludes: "The nature of the material record tends to raise more questions than it answers; the complicated data and various interpretations thus must be treated with a critical eye" (ibid:14).