|

CONTENTS KEY

1. Introduction

2. Reincarnation Claim of Sathya Sai

3. Birth Theories are not Conclusive Evidence

5. Urdu Notebook of Abdul Baba

6. Dakshina

8. Universalism and Zoroastrians

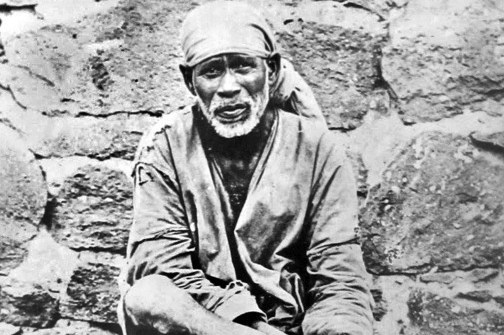

Shirdi Sai Baba (d.1918) is distinctive for an inter-religious complexion. The diverse Hindu and Muslim aspects of his biography have aroused enthusiasm, speculation, incredulity, and repudiation. The full background data has rarely been assimilated. Many coverages tend to abbreviation in this respect. In India, there are now very numerous Shirdi Sai devotees, and also some Hindu critics who react to the Muslim Sufi features discernible. My own book, Sai Baba of Shirdi: A Biographical Investigation (2015), acknowledged both the Hindu and Sufi components of the subject's profile. In what follows, I will cover some of the relevant topics for consideration.

2. Reincarnation Claim of Sathya Sai

Newcomers to the subject are sometimes puzzled by the existence of two Sai Babas, meaning the two entities known as Shirdi Sai Baba and Sathya Sai Baba (d.2011). The latter created the wealthy Puttaparthi ashram in Andhra, and early claimed to be the reincarnation of Shirdi Sai. This claim is dismissed by followers of the Shirdi saint. They point out that Sathya Sai gained much fame as a result of his reincarnation theme. The Puttaparthi guru adopted the name Sai Baba as his own (his real name was Ratnakaram Satyanarayana Raju). This situation produced in America an influential theory of a supposed Sai Baba movement. Sathya Sai also innovated a mythology of the Shirdi saint, presenting the faqir as an incarnation of Shiva (Rigopoulos 1993:21-27). This lore became part of Sathya Sai's explicitly declared (and controversial) profile as an avatar. Various other critics, including Basava Premanand, have lodged complaints at the exhibition of purported miracles on the part of Sathya Sai.

3. Birth Theories are not Conclusive Evidence

The origins of Shirdi Sai are obscure. His date of birth is unknown. Various dates have been suggested, but none of these are confirmed. A major source, the Shri Sai Satcharita, relays that Shirdi Sai was about eighty years old when he died in 1918. However, a birth date in the 1850s was suggested by other commentators. A well known version, by a British writer, stated that Sai Baba "first appeared in the little town of Shirdi as a lad of about sixteen in 1872" (Osborne 1958:13). A prudent conclusion has been: "The date of birth that is given most frequently is 1838, although the precise year is impossible to verify independently from this distance in time" (Warren 1999:36).

In the late twentieth century, an influential theory favoured Pathri as the birthplace of Sai Baba. This town was formerly situated in the dominion of the Nizam of Hyderabad. Furthermore, V. B. Kher speculated that Shirdi Sai was born a Hindu at Pathri, and more specifically, a deshastha brahman of the Bhusari family. The chosen deity of that family was Hanuman (Maruti). Kher associated this factor with the respect awarded to Maruti by Sai Baba (Kamath and Kher 1991:14-18). However, there is no proof that this theory is correct, despite enthusiastic support.

Another theory is that Sai Baba was born in Jerusalem. This version is associated with a Hindu lawyer, who made allowance for Muslim associations of the Shirdi faqir. The legend credits the parents of Sai Baba as being Vaishnava brahmans of Gujarat, who are said to have visited Mecca in the company of a Muslim faqir. Different versions of the same legend affirm the date of birth for Sai Baba as 1836 and 1858 respectively (Shepherd 2005:4-5).

At the village of Shirdi, in Maharashtra, Sai Baba was early identified as a Muslim faqir. The reasons are straightforward and quite obvious. He wore the standard garb associated with Muslim faqirs, meaning a white kafni and matching headgear. He spoke in Deccani Urdu, a Muslim language. He took up residence in a local mosque, where he remained for decades until his death. He could frequently be heard uttering Islamic phrases such as "Allah Malik."

However, Sai Baba did not promote Islam. He did not preach any religious doctrine, being remarkably neutral in this respect. Some writers describe him as a Sufi; there are different interpretations of this identity (Shepherd 2015:22-37). Sai Baba was not an orthodox Sufi, as the record reveals.

The category of faqir included diverse representatives, varying from superficial exhibitionists to more committed ascetics. The faqir lifestyle, of poverty and abnegation, dates back to the early centuries of Islam. Shirdi Sai Baba demonstrated a strong ascetic orientation, continuing to beg his food daily in Shirdi, living in a very simple manner.

Depiction of Sai Baba performing ablutions at the Shirdi mosque |

This faqir was in the habit of regular ablutions. Shirdi Sai was not an emaciated ascetic, instead possessing a solid physique. His diet from the begging round was bread and vegetables; according to the available record, he supplemented with meat and fish when in the company of Muslims.

Despite a number of Muslim Sufi characteristics, Sai Baba early resisted a group of local Muslim militants who objected to the appearance of Hindu worship at the Shirdi mosque. The agent for this worship was Mhalsapati, a priest who had formerly been averse to the faqir, regarding him as an outsider to Hindu temples. The militants summoned the Qazi of Sangamner to assist their cause. They armed themselves with clubs. Their leader threatened the timid Mhalsapati. Sai Baba transpired to be in support of Mhalsapati, defying the orthodox mood of censure. This event apparently occurred in 1894.

Worship (puja) thereafter occurred at the mosque on a very small scale, later becoming a more visible feature of collective worship in the saint's last years. Sai Baba then permitted arati rites of devotion for a predominantly Hindu following. There were four arati performances daily from 1910, and two of these were allowed in the mosque precincts. The other performances occurred at the dilapidated building known as chavadi, formerly used for village activities (Shepherd 2015:128-130, 213-217).

A process of Hinduisation has been detected in the literature about Shirdi Sai. The basic accusation is that Muslim elements of the Shirdi Sai biography were marginalised. The Shirdi saint has been viewed as representing a trend to religious syncretism, occurring for centuries in Maharashtra (Warren 1999:130-194). In that respect, a symbiosis between Sufism and Bhakti Hinduism emerges.

5. Urdu Notebook of Abdul Baba

A significant document was not translated until eighty years after the death of Shirdi Sai. This document confirms that Sai Baba expressed himself in Urdu as a Muslim Sufi.

The Urdu Notebook was translated into English by Urdu specialists, and mediated in a book by Dr. Marianne Warren. This document is still widely unread. The Notebook comprises jottings from the pen of Abdul Baba, an early follower who arrived at Shirdi in 1889. Abdul himself lived as a faqir. His jottings relay utterances of Sai Baba, attesting a familiarity with Islam and Sufism. Some passages are quite distinctive, revealing Sai Baba as a radical critic of some dubious trends amongst faqirs and orthodox Sufis. The Shirdi saint also accuses mullas and qazis of accepting bribes.

Someone pretends to become a pir [Sufi adept], showing his skills, attracting and influencing people in order to fill his coffers and amass wealth. (Warren 1999:306)

Sai Baba was not guilty of hoarding riches. He did not adopt the role of a Sufi pir, being far more elusive in terms of identity.

During the last decade of his life, Sai Baba gained many Hindu devotees. These people basically represented an urban following, many coming from Bombay (Mumbai), also other cities and towns. A fair number of them were evidently wealthy. There were also visitors who came for reasons of curiosity, or who desired the mundane and spiritual benefits believed to be acquired via gaining the darshan (meeting) of a saint.

In response to this influx of visitors, the Shirdi faqir innovated a habit of asking for dakshina, meaning a gift of money. The amount requested would vary considerably. Some visitors were not asked for the gift, even if they wished to make a contribution. Sai Baba never kept any of the money he obtained in this manner. Instead he gave away all the incoming funds by nightfall. The recipients were diverse local inhabitants, including ascetics and devotees. At his death, Sai Baba had no money or assets. The redistribution feat is memorable. There were critics who said that ascetics should never ask for money.

The numerous Hindu devotees represented a wide range of different temperaments. Some of the urban supporters were civil servants and officials, including Nanasaheb Chandorkar, who became celebrated for prompting Sai Baba to give a distinctive (and controversial) interpretation of a verse from the Bhagavad Gita.

Another prominent devotee, from Bombay, came to reside at Shirdi in 1916. Govind R. Dabholkar (d.1929) was a former magistrate. He composed in Marathi the Shri Sai Satcharita, a lengthy poetic work recording diverse anecdotes and reminiscences of Sai Baba, together with a commentary.

After the death of Sai Baba, two of the more well known devotees became sannyasins. One of these was Thoser, alias Swami Narayan (Shepherd 2015:238-240). The other was Swami Sai Sharan Anand, originally known as Vaman Patel, who stayed at Shirdi for nearly a year during 1913-14. Anand believed that Sai Baba was a Hindu, more specifically a brahman. Anand eventually authored in Gujarati the book entitled Shri Sai Baba. Before he first encountered Sai Baba in 1911, Anand attended Elphinstone College in Bombay. There he studied Western philosophy under a European tutor, a scholar of German and Greek. "The study of Kant's philosophy unsettled Vaman's mind and he wondered whether God really existed or was merely the creation of man's mind; whether the universe was sustained by a conscious creative power or was created accidentally" (Anand 1997:xiv, sketch by V. B. Kher).

Balasaheb Bhate studied at the Deccan College (near Poona), early committing himself to materialist scepticism (Shepherd 2015:118). Becoming a revenue officer near Shirdi, he ridiculed Sai Baba as a madman, being influenced by adverse rumour. When Bhate afterwards visited the faqir at Shirdi in 1909, he found that the situation was not as he had imagined. The sceptic was never the same again. After only five days, his attitude changed totally. Bhate thereafter became a resident devotee at Shirdi.

Ganesh Khaparde first visited Shirdi in 1910, afterwards staying for a few months. He commemorated Sai Baba in his diary. His intimate descriptions of the faqir reveal a multi-faceted character, who favoured parables instead of lectures or discourses. Khaparde was a lawyer and politician, closely associated with the radical Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who visited Shirdi once, in 1917, along with Khaparde (Shepherd 2015:259-262). Khaparde was a supporter of Sai Baba, whereas Tilak made the visit after persuasion.

Upasani Shastri, known as Maharaj (1870-1941) was an unusual disciple of Sai Baba. Appearing at Shirdi in 1911, Upasani thereafter stayed at the instruction of Sai in the nearby Khandoba temple, the scene for many unusual events. He eventually established his own ashram at nearby Sakori, where he established the Kanya Kumari Sthan for Hindu nuns.

B. V. Narasimhaswami did not become a supporter until 1936, having transited from the career of a lawyer to the lifestyle of a sannyasin. His tendency was thereafter to become a missionary figure, touring India and giving talks on Sai Baba. Narasimhaswami (d.1956) exerted a strong influence upon the formative Shirdi Sai movement. In the book Devotees' Experiences, he recorded an extensive set of 1930s interviews with surviving Sai devotees and related persons. His multi-volume Life of Sai Baba awards a disconcerting importance to miracles; however, the hagiology is accompanied by other materials of factual relevance (Shepherd 2015:328-337).

8. Universalism and Zoroastrians

The inclusive religious attitude of Shirdi Sai extended to Zoroastrians, a number of whom became followers. They were a minority compared to the Hindu devotees. Only one Zoroastrian was living in Shirdi at the time of the faqir's death. This was Gustad Hansotia (d.1958), a Parsi who escaped reporting in the well known Hindu sources. He had been a devotee since 1910, living in Bombay (Shepherd 2015:272-276). After the death of Sai Baba, Gustad became a disciple of Meher Baba (1894-1969), who created two ashrams near Ahmednagar. Meher Baba had also visited Shirdi, afterwards expressing a high estimation of the distinctive faqir.

Anand, Swami Sai Sharan, Shri Sai Baba, trans. V. B. Kher (New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 1997).

Dabholkar, Govind R., Shri Sai Satcharita: The Life and Teachings of Shirdi Sai Baba, trans. Indira Kher (New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 1999).

Kamath, M. V., and Kher, V. B., Sai Baba of Shirdi: A Unique Saint (Bombay: Jaico Publishing House, 1991).

Khaparde, Ganesh S., Shirdi Diary of the Hon’ble Mr. G. S. Khaparde (Shirdi: Sri Sai Baba Sansthan, n.d.).

Narasimhaswami, B. V., Devotees’ Experiences of Sri Sai Baba (3 vols, Madras: All India Sai Samaj, 1940).

--------Life of Sai Baba (4 vols, Mylapore, Chennai: All India Sai Samaj, 1955-6).

Osborne, Arthur, The Incredible Sai Baba (1957; London: Rider, 1958).

Rigopoulos, Antonio, The Life and Teachings of Sai Baba of Shirdi (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993).

Shepherd, Kevin R. D., Investigating the Sai Baba Movement (Dorchester: Citizen Initiative, 2005).

--------Sai Baba of Shirdi: A Biographical Investigation (New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 2015).

--------Sai Baba: Faqir of Shirdi (New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 2017).

Warren, Marianne, Unravelling the Enigma: Shirdi Sai Baba in the Light of Sufism (New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 1999).

Copyright © 2021 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved. Uploaded 2016, last modified June 2021.